Robert's blog 'On Photography'

'On Photography' is a blog that explores the relation and controversies between professional photography, art and awareness.

Your comments and involvement are highly appreciated.

This website also serves as an archive of events organised by Robert Schilder.

Project: Glasgow Architects

The idea was to make projections on the other side of the street (then a quite uninteresting carpark), large posters (for instance from exhibitions and cultural events) and coloured light ( as for instance the (then) PTT building in the Hague (NL) ) I remember it took me a night, the idea was never realised, but it was sure nice to work on!

Curating photography

Interview with Peter GALASSI, Former Chief Curator of Photography, MoMA, New York

By Daniel Palmer – Published: 25/08/2016

"The biggest thing that happened, and what defined the biggest challenge of my twenty years as Chief Curator, was that photography’s indigenous traditions, photographic traditions, were joined by a new tradition of photography within the contemporary art world. It really began to take shape in the 1960s, and by the late 1970s was a real force to be contended with."

"The other big challenge was that we’re now towards the end of the golden age of collecting"

"Well I think of Steichen as an aberration in an otherwise normal history of a museum. You know Steichen was a great artist, he was a great artist at least twice over, but by the time he came to MoMA he was a person who always wanted to be at the centre of things. And his perception, beginning sometime in the 1930s, was that the centre of things was the magazine business – photography as mass communication. He set out to be a big player in that world and at MoMA that’s what he was, he was like Life magazine inside the walls of the museum. "

"I think Szarkowski is still, by a long shot, the best curator and historian photography has had, so far. But that doesn’t mean he was always right. He was unresponsive to a certain swath of activity, that’s for sure. Of course, curators have a responsibility that artists don’t have, nevertheless, you judge artists on their best work, not on their average work. So if you judge Szarkowski on his best work, no other curator’s done that well. And after all, now that the dust is settling on this, if you had to pick the three most important photographers, the three most important artists who made photographs in the 1960s – Winogrand, Friedlander, Arbus…"

I am so tired of hearing about how digital technology has destroyed photography’s connection to the real world, that I’m thinking about organizing a show about all the ways that digital technology has enhanced photographers’ abilities to be involved in the real world.

Interview conducted in October 2013 photocurating.net/peter-galassi/

A triangle

Try to see it as a triangle, with 3 persons or parties at the corners:

1. is the hard working photographer, the artist if you like with definite ideas and motivation.

2. is the one who is in the picture, the sitter, what is the sitter's expression or how do people react when their picture is taken? Are they aware of the camera / photographer? Do they connect with the photographer's idea?

3. Than there is the spectator, looking at the final portrait, to consider, who has his own opinion of the contents.

Another example of this 'triangle' is this:

1. what you say must have meaning

2. there must be someone who listens

3. that person must do something with what you are saying

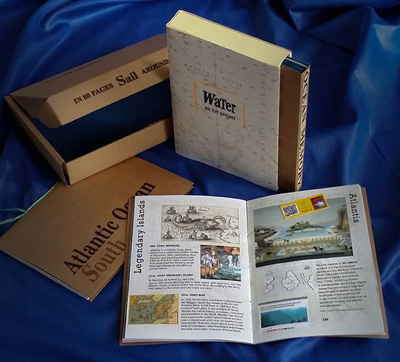

'WATER'-een kunstprojekt: Zeilen op de Atlantische Oceaan

nederlandse tekst:

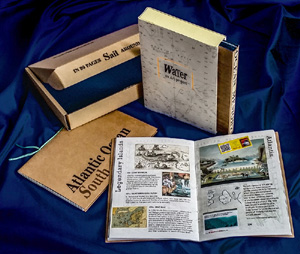

2 boekjes en een 'Memory Game' vormen samen een promotie set voor een internationale fotografie tentoonstelling over WATER. De boekjes -of reisjournalen- zijn handgemaakt en handgebonden, verpakt in een hoesje met een originele zeekaart zoals die is gebruikt tijdens de zeiltocht met de 'Gemini'.

De 2 boekjes bevatten achtergrondinformatie over de plaatsen, geschiedenis, die wij hebben aangedaan. Het eerste boekje gaat over de zeiltocht van Simonstown in Zuid Afrika naar Fortaleza in Brazilië. Het tweede boekje gaat over de tocht van Sint Maarten in de Cariben naar Nederland.

De 'Memory Game' (ter 'leering ende vermaeck') is net als de twee boekjes door nummers verbonden met een website waar alle gegevens van het onderzoek, wat is gedaan voor het project, op staan.

english text:

WATER -an art project

2 long sailing trips on the Atlantic Ocean were the reason for my fascination with WATER, ocean and discovery and the start of a thorough research. Project's aim is an exhibition of art photography which will travel the world and a book "SAIl- around the world in 80 pages"

2 booklets and a 'Memory Game' form together the promotion pack for this project. They are handmade, handbound and packed together in a case with a jacket made from an original nautical chart as used during our voyage with sailing yacht 'Gemini'.

The first booklet 'South Atlantic Ocean' gives more information about countries and places we visited from Simonstown in South Africa to Fortaleza in Brazil.

The second booklet 'North Atlantic Ocean'', covers Sint Maarten in the Caribbean to the Netherlands and has also more information about our living ocean as an environment.

The 'Memory Game' will test your memory and knowledge about some of the topics from the project.

Numbers in the book link directly to a website with much more information (www.water-artproject.com/resources.html). Because of the size of this webpage it may be easier to download a pdf file here: www.WATER-artproject.com/water-artproject-resources.pdf

Detailed information about the actual sailing can be found on these two websites: 2014sail2015.wordpress.com (English) and www.sy-gemini.nl (in Dutch).

The Art Photography has been created in such a way -by layered printing, combining images and unique techniques- that the works become 3-dimensional. they all measure 120 x 70 cm., framed and packed in flight cases, ready to travel the world!

For more information please contact:Robert Schilder

Turkeye 6

4508PB WATERLANDKERKJE

The Netherlands

+31-6-21138318

robertschilder@gmail.com

AI & Phot. part I: Computer vision, human senses, and language of art

Manovich, Lev (2020). Computer vision, human senses, and language of art. AI & Society. doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01094-9

manovich.net

tags: Computer vision, Digital humanities, Cultural analytics, Language of art, artificial intelligence, lev manevich

In the original vision of artificial intelligence (AI) in 1950s, the goal was to teach computer to perform a range of cognitive tasks. They included playing chess, solving mathematical problems, understanding written and spoken language, recognizing content of images, and so on. Today, AI (especially in the form of supervised machine learning) has become a key instrument of modern economies employed to make them more efficient and secure: making decisions on consumer loans, filtering job applications, detecting fraud, and so on.

What has been less obvious is that AI now plays an equally important role in our cultural lives, increasingly automating the realm of the aesthetic. Consider, for example, image culture. Instagram Explore screen recommends images and videos based on what we liked in the past. Artsy.net recommends the artworks similar to the one you are currently viewing on the site. All image apps can automatically modify captured photos according to the norms of "good photography." Other apps "beatify" selfies. Still other apps automatically edit your raw video to create short films in the range of styles. The App The Roll from EyeEm automatically rates aesthetic quality of you photos (...)

Does such automation leads to decrease in cultural diversity over time? For example, does automatic edits being applied to user photos leads to standardization of “photo imagination”? As opposed to guessing or just following our often un-grounded intuitions, can we use AI methods and large samples of cultural data to measure quantitatively diversity and variability in contemporary culture, and track how they are changing over time?

manovich.net/index.php/projects/automating-aesthetics-artificial-intelligence-and-image-culture

All Items from the GARAGE SALE'

gar0001 PCS Arsat H 1:2,8 35mm Shift Lens

gar0002 teaset from the Orient

gar0003 Linhof folding camera

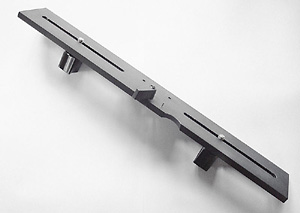

gar0004 extension rail Sinar

gar0005 Broncolor backgroundprojector

gar0006 PROF. EQUIPMENT: 6x9 rollfilm holder for 4x5”view cameras

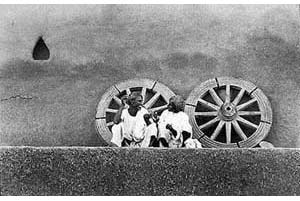

gar0007 STOCK PHOTOGRAPHY: the Banaras files

gar0008 PROF. EQUIPMENT: Sinar F1

gar0009 GARAGE SALE: Dexter Mat cutter

gar0010 PROF. PHOTO EQUIPMENT: 8x10"cassettes

gar0011 PROF. PHOTO EQUIPMENT: 18x24 cm. cassettes

gar0012 CIRCLE-24

gar0013 the 1990’s: Trends in Photography and Graphic Design

gar0014 PROF. EQUIPMENT: sturdy lampstand

gar 0015 GARAGE SALE: Scart items

gar0016 PROF. EQUIPMENT: Niethammer spotlight with flash (sold)

aerial disk

Prefer Electret Condensor Microphone

link to Background stock phot.

Photography for Sale booklet

gar0021 “Your Advertisement could be here!!”

gar0022 WATER-project: “2 handbound travel Journals and a Memory Game”

stock photos of Architecture

gar0024 Prof. Equipment: Apo Ronar lens 480mm 1:9

the Awareness files

gar0026 PROF. EQUIPMENT – Background Projection Screen

Hosemaster Light painting equipment (sold)

Broncolor extension cable

Sinar to Slr bracket

large lampstand

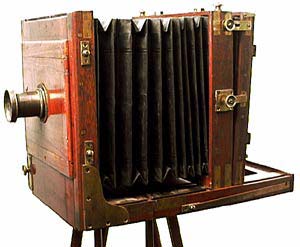

wooden camera from Chor Bazaar

Broncolor / Pulso lamp mount

Kodak Register punch

Boroncolor Flashmeter

lamp draai kop broncolor vatting

black lampstand

Broncolor Pulso Flooter (sold)

Kodak Photo CD

Broncolor Impact spot cone

Cullmann Tripod

lampstand robust

Scuba flash

Panagor Zoom duplicator

Ryger 403PRO

contra weight +swivel

remote + cable Caroussel

extention cable Caroussel

adsl

small binocular

porthole

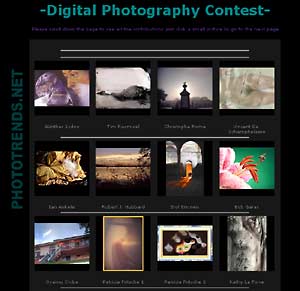

Digital Photography Contest

ceiling attachment Broncolor

painting set

Nikon F801 with lens

Rodenstock Sironar-N 360

Haliburton suitcase with Hasselblad equipment

SINAR camera (ask)

SINAR F

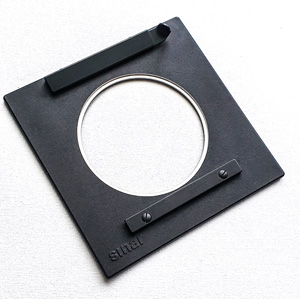

SINAR F Standard accessory Frame with 2 shade barn doors on a detachable frame

gar0068 PROF. EQUIPMENT: SINAR P-format 8x10” adapter (sold)

gar0076 PROF. EQUIPMENT: Sinar zoom cassette

objectief Sironar NMC 5.6/135 mm. nr.9561390

objectief Apo-Ronar 300 mm. 1:9

Swiss 'CAMERA' magazine

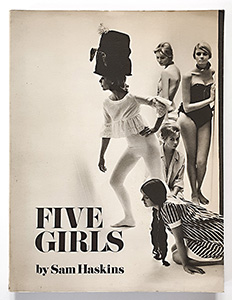

Sam HASKINS: "Five Girls"

Ilford Multigrade 500 vergrotingsapparatuur

Gitzo Rationelle Plus

Broncolor Unilamp incl.flitsbuis

set lampen Impakt Expert Kit

lightmeter Broncolor FM

gar0097 Broncolor FCM meetsonde

Sony cassetterecorder 103650

Kostiner vergrotingsbord

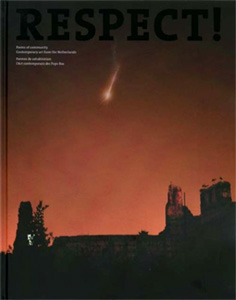

‘Respect! Forms Of Community. Contemporary Art

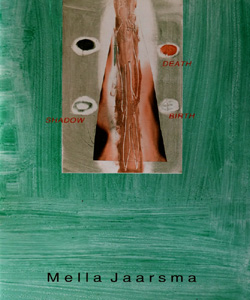

gar0101 BOOKS: ‘Mella Jaarsma portfolio catalogue’

gar0102 BOOKS: Krzysztof Sroda 'photographies'

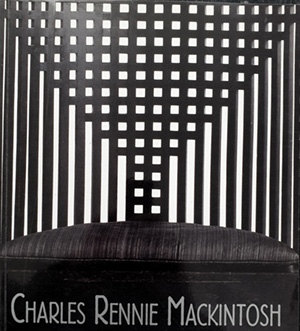

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

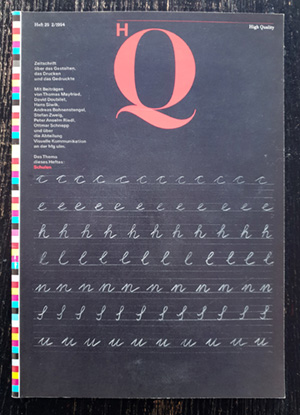

Quote magazine

Ryszard Horowitz calendar 1999

Stones in the Road, Photographs of Peru

CONSTANT: New Babylon, Aan ons de vrijheid

Crafts reforming in Kyoto (1910-1940)

Boymans van Beuninegen

Toni Meneguzzo 'Seduzioni'

Friesland is ..

Pour une histoire de la photographie en Belgique

Paul GRAHAM "New Europe"

Advertising Photography in Japan 6

Lancome

Krzysztof Sroda photographies

Schatzhaüser der Photographie"

Stray dogs

BANARAS, city of Gods, heart of India

Picturing modernity

Ryszard Horowitz

The Awards 25

The Awards 24

Hugo Erfürth, Photograph zwischen Tradition und Moderne

Photographers on photography

the Red River

Tokyo, a city perspective

50 Years modern color photography / 50 Jahre moderne Farbfotografie 1936-1986.

Alfred Stieglitz & Yazuso Nojima

Germaine Krull, Avantgarde als Abenteuer

Fotografie als Kunst

Das Endlose Rad

Pour la Liberté de la Presse

My World PH-KLM

Tank Issue #5, July 1999

La Hollande

Seasons of Light, images of Ontario

Photographers photographed

Europe

Notations in Passing

4x the IMAGE

My experiences in colour photography

Slides, planning and producing slide programs

Entre deux

Photoshop 5.0

Edward Weston, his life

Frantisek Drtikol, art-deco photographer

La Danse

gar0149 BOOKS: the Ambiguous Image

gar0150 BOOKS: Heartbeat, Machiel BOTMAN

gar0151 BOOKS: Teun VOETEN: ‘A ticket to’

gar0152 ‘Art & Photography’ Aaron SCHARF

gar 0153 BOOKS: : ‘the Science of Photography’ H.BAINES / E.S.BOMBACK

gar0154 BOOKS: ‘Albert RENGER PATCH, Meisterwerke’

gar0155 BOOKS: "Advertising Photography in Japan #6"

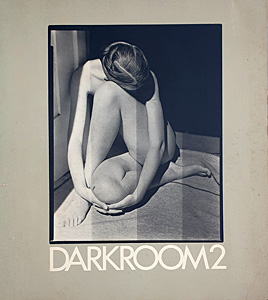

gar0156 BOOKS: ‘History of the nude in photography’ -Peter LACEY

gar0157 BOOKS: ‘The ferrotype and how to make it’

gar0158BOOKS: ‘Images, images, images’

gar0159 BOOKS: ‘Other than Itself’

gar0160 BOOKS: ‘Conceptual Still Life Photography’

gar0161 BOOKS: "Publishing Photography"

gar0162 BOOKS: ‘Starting Photography’ Michael LANGFORD, Focal Press

gar0163 BOOKS: "the PC & MAC handbook" Steve HEATH

gar0164 BOOKS: "World of Energy"

gar0165 BOEKEN: Hubert LAMPO & Pieter Paul KOSTER 'Arthur"

gar0166 ‘Dialogue with Photography’

gar0167 BOEKEN: "Het huis van het Midden" Rommert Boonstra

gar0168 BOOKS: ‘Nichts wird uns Trennen’ Tim BESSERER

gar169 BOOKS: portfolio Ki Ho Park

gar170 BOOKS: "the Camera in Commerce"

gar0171 BOOKS: "Ralph Eugene Meatyard"

gar0172 ‘Stones in the Road’ Nubor ALEXANIAN

gar0173 BÜCHER: ‘Feindbilder’ Peter HEBEISEN

gar0174 BOEKEN: Rommert BOONSTRA: ‘Natura ex Machina’

gar0175: BOOKS: Leni RIEFENSTAHL, Schönheit im Olympischn Kampf

Aditi: The Living Arts of India

gar0177 BOEKEN: ‘Oeververbindingen’

gar0178 BOOKS: " Treasures of the Royal Photographic Society"

gar0179 BÜCHER: ‘das xx.jahrhunderteinjahrhundert kunst in deutschland’

gar0180 BOOKS: Special effects Photography

gar0181 BOOKS: Kiyoji Ohtsuji

gar0182 BOOKS: ‘Dutch Design 1998 / 1999’

gar0183 BOOKS: ‘Branding with Type’

gar0184 BOEKEN: Beeldschermtypografie

gar0185 BOOKS: ‘100 Keywords For Understanding Japan?’

gar0186 BOOKS: ‘Gustav Klimt’

gar0187 BOEKEN: ‘Sprekende Theaterbeelden’

gar0188 BOOKS: ‘Passages, Joris Ivens en de kunst van deze eeuw’

gar0189 BOOKS: ‘Into the Silent Land’

gar0190 BOOKS: ‘the photography of Sunmi Smart Cole’

gar0191 BOEKEN: ‘Bericht 3’

gar0192 BOOKS: Photography Today, ´the Absence of Distance´

gar0193 LIVRES: "Propos sur la Photographie"

gar0194 LIVRES: Régis DURAND: "le Monde aprés la Photographie"

gar0195 BOOKS: Carleton WATKINS, 'the Art of Perception'

gar0196 BOOKS: "Contemporary photographic portraiture"

gar0197 BOOKS: Eldad MAESTRO ‘Fields’

gar0198 BOEKEN: Fotografie als Kunst 1904 "Het Landschap"

gar0199 BOOKS: Real World Photoshop 3.0

gar0200 BOOKS: ‘Les Papous’ Malcolm KIRK

gar0201 BOOKS: ‘Odilon Redon’

gar0202 BOOKS: A Collection Sculptures

gar0203 BOOKS: ‘Tumarin’

gar0204 BOOKS: ‘George Grosz’

gar0205 BOOKS: Art & Visual Perception Rudolf ARNHEIM

gar0206 BOOKS: Nederlands Ontwerp / Dutch Design 1998 / 1999

gar0207 Magnum Zukunft ohne Stil

gar0208 BOOKS: Japanese Glass

gar0209 Japans met ronde bol

gar0210 BOEKN: 'Sprekende theaterbeelden';

gar0211 BOOKS: Tokyo Perspective

gar0212 BOEKEN: N 52° 00.000' E 005° 00.00

gar0213 BOOKS: ‘Breaking Tradition’

gar0214 BOOKS: ‘Patterns and Colors of Joy’

gar0215 BOOKS: ‘Zugriff – Spirited Approach’

agar0216 LIVRES: ‘Azimuts', revue de design 15/1998’

gar0217 BOOKS: Designer Profile 1998/1999

gar0218 BOEKEN: ‘"Beeldschermtypografie"

gar0219 BOOKS: Designer Profile 1998/1999 Deutschland Österreich Schweiz

gar0220 BOOKS: ‘Art Nouveau and art deco ceramics‘

gar0221 BÜCHER: Günther Grass ‘In Kupfer auf Stein’

gar0222 BOOKS: Dutch Posters 1960 - 1996

gar0223 'the Bauhaus in Calcutta' An Encounter of the Cosmopolitan Avant-Garde

gar0224 Presence, photographs by Clement COOPER

gar0225 BOEKEN: Ommuurde dromen

gar0226 BOKS: Where qualty meets

gar0227 BOOKS: Advertising photography in Japan 2000

gar0229 BOOKS: ‘How to run a successful design company’ Marcello MINALE

gar0230 BOOKS: Paolo Gioli fotografie, dipinti, grafica, film

gar0231 the Indian tapes VHS Video tapes

gar0232 BÜCHER: 'Eine Anleitung zum SelbstEntwickeln Der Ferraniacolor-Tageslicht-Umkehrfilme'

Fotografia Buffa

gar0234 Gift package with 5 Discovery / Sailing Related Artcards

gar0235 WATER Art Project: 2 handmade / handbound travel journals and a Memory Game

gar0236 BOEKEN: Reproduktiefotografie

gar0237 Brassaï Paris Taschen

gar0238 BOEKEN: Mijn Roofvogels, Rob BIJLSMA

gar0239 BOEKEN: ''Paris Mortel Johan VAN DER KEUKEN

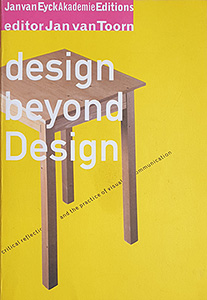

gar0240 Design beyond Design, Jan van TOORN